Background

The Golaknath vs State of Punjab case (1967) was a landmark judgment of the

Supreme Court of India that fundamentally shaped the relationship between

Parliament and the Constitution. This case dealt with the question of whether

Parliament had the power to amend Fundamental Rights enshrined in Part III of

the Constitution. It arose at a time when India was undergoing significant

social and economic reforms involving land redistribution and curtailment of

property rights to advance social justice. The judgment reflected the tension

between the Parliament’s authority to implement reform measures and the

judiciary’s role in safeguarding constitutional rights.

The background of this case lies in earlier constitutional amendments that sought to place land reform laws in the Ninth Schedule to protect them from judicial review. The property owners, including the Golaknath family from Punjab, challenged these amendments, claiming that their fundamental right to property under Article 19(1)(f) and Article 31 was being violated.

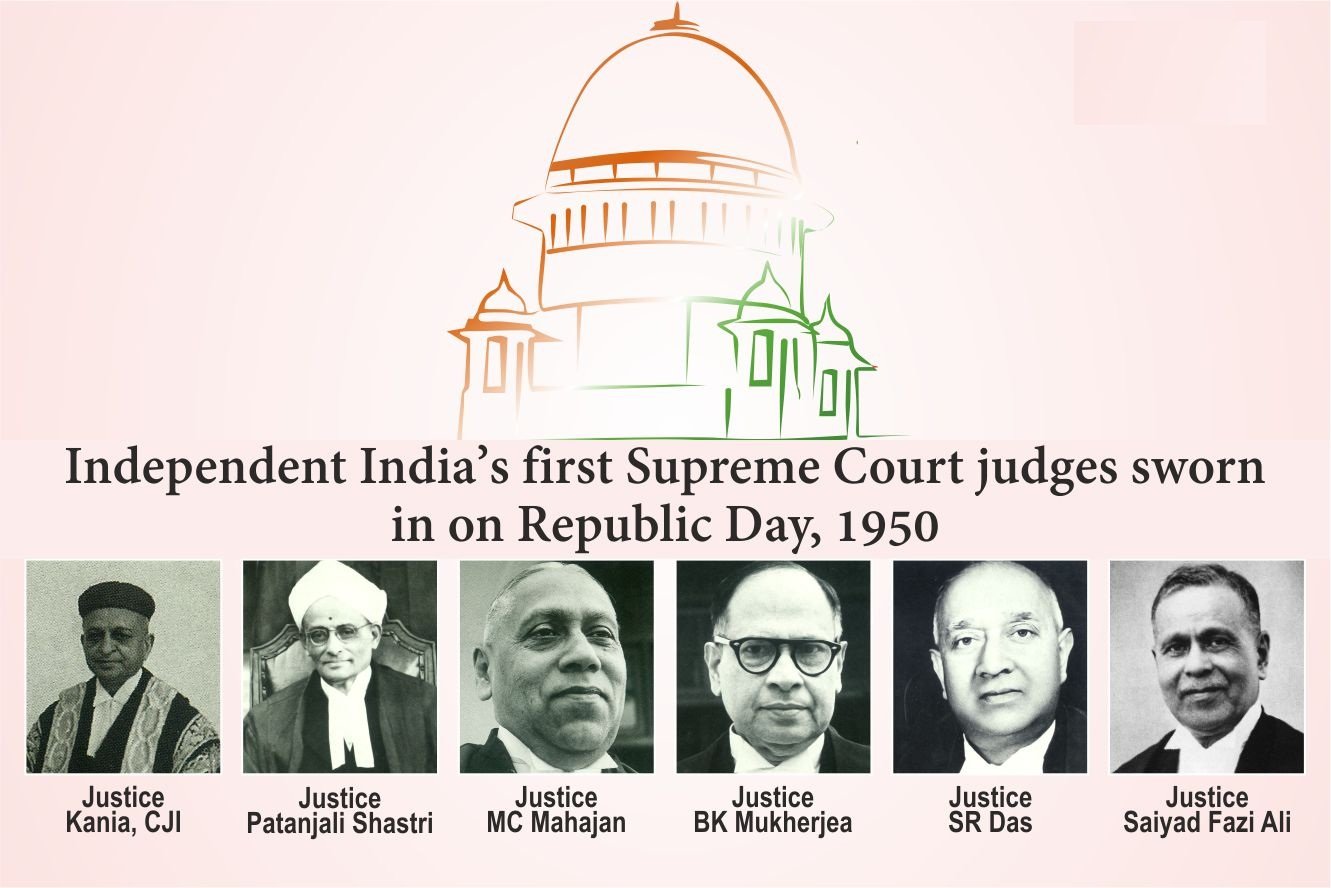

The case was heard by an eleven-judge bench, with a narrow majority of six to five delivering the ruling that Parliament could not amend or abridge Fundamental Rights. It marked a turning point in India’s constitutional evolution and later led to the concept of the Basic Structure Doctrine in 1973 through the Kesavananda Bharati case.

Important Facts for Prelims Exams

- Year of Judgment: 1967

- Bench Strength: 11 judges (6:5 majority)

- Petitioners: Henry and William Golaknath (Punjab)

- Respondent: State of Punjab

- Articles Involved: Articles 13, 32, 368

- Key Question: Can Parliament amend Fundamental Rights under Article 368?

- Outcome: Parliament cannot amend Fundamental Rights.

- Later Development: Overruled by Kesavananda Bharati case (1973) establishing the Basic Structure Doctrine.

Main Provisions and Key Facts

- The case originated when the Punjab Government acquired agricultural land belonging to the Golaknath family under its land reform laws.

- The petitioners claimed that this acquisition violated their Fundamental Rights.

- The Supreme Court reviewed the validity of the 1st, 4th, and 17th Constitutional Amendments.

- These amendments had placed various land reform laws under the Ninth Schedule, making them immune from judicial review.

- The majority judgment (led by Chief Justice Subba Rao) held that Fundamental Rights are ‘transcendental and immutable’ and cannot be abridged by Parliament.

- The Court ruled that Article 368 only lays down the procedure for amendment but does not grant the power to amend Fundamental Rights.

- It further observed that any amendment that curtails Fundamental Rights would be void under Article 13(2).

- The judgment recognized the duty of the judiciary to preserve the sanctity of the Constitution and protect citizens’ rights.

- The minority view (led by Justice Wanchoo) argued that there was no restriction on Parliament’s amendment powers.

- This case created a temporary bar on constitutional amendments affecting Fundamental Rights.

Significance

- Reinforced the supremacy of Fundamental Rights as essential and unalterable parts of the Constitution.

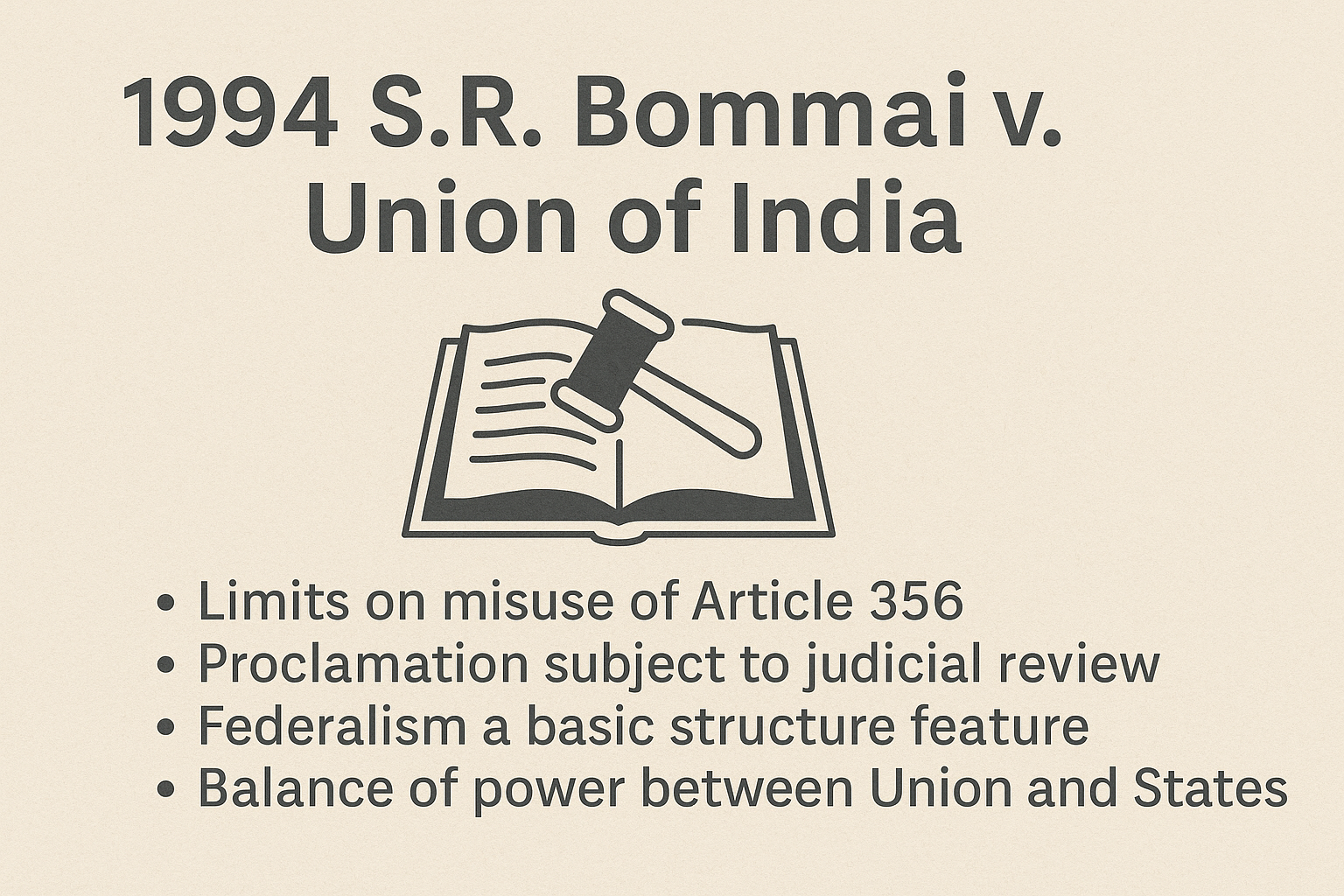

- Marked the beginning of the judicial doctrine that eventually led to the Basic Structure concept in Kesavananda Bharati (1973).

- It limited Parliament’s amending power temporarily, emphasizing constitutional permanence and checks on legislative authority.

- The judgment reflected the evolving balance between judicial review and parliamentary sovereignty.

- Ensured that social and economic reforms must respect constitutional rights.

- Demonstrated the strength of India’s democratic and constitutional framework by sustaining open debate between judiciary and legislature.

Criticism or Limitations

- The judgment was criticized for restricting Parliament’s ability to implement socio-economic changes.

- It led to a constitutional deadlock between the legislative and judicial branches.

- To overcome this, the 24th Amendment (1971) was introduced, clearly stating that Parliament had the power to amend any part of the Constitution, including Fundamental Rights.

- Some constitutional experts argued that the judgment blurred the line between interpretation and judicial legislation.

- Later, the Supreme Court in Kesavananda Bharati (1973) balanced this by recognizing that Parliament could amend the Constitution but not alter its basic structure.

Key Points for Exams

- Year: 1967

- Articles: 13, 32, 368

- Constitutional Amendments Involved: 1st, 4th, 17th

- Bench: 11 judges (6:5 majority)

- Chief Justice: K. Subba Rao

- Doctrine Involved: Precursor to the Basic Structure Doctrine

- Overruled by: Kesavananda Bharati Case (1973)

- Impact: Restricted parliamentary amendment powers temporarily

- Significance: Assertion of judicial review over legislative powers

- Objective: Preservation of Fundamental Rights

The 1967 Golaknath vs State of Punjab case held that Parliament could not amend Fundamental Rights, establishing judicial supremacy in protecting citizens’ rights. It laid the foundation for the later development of the Basic Structure Doctrine, which continues to guide constitutional interpretation in India.

Comments (0)

Leave a Comment